DesignEducationDecolonisation

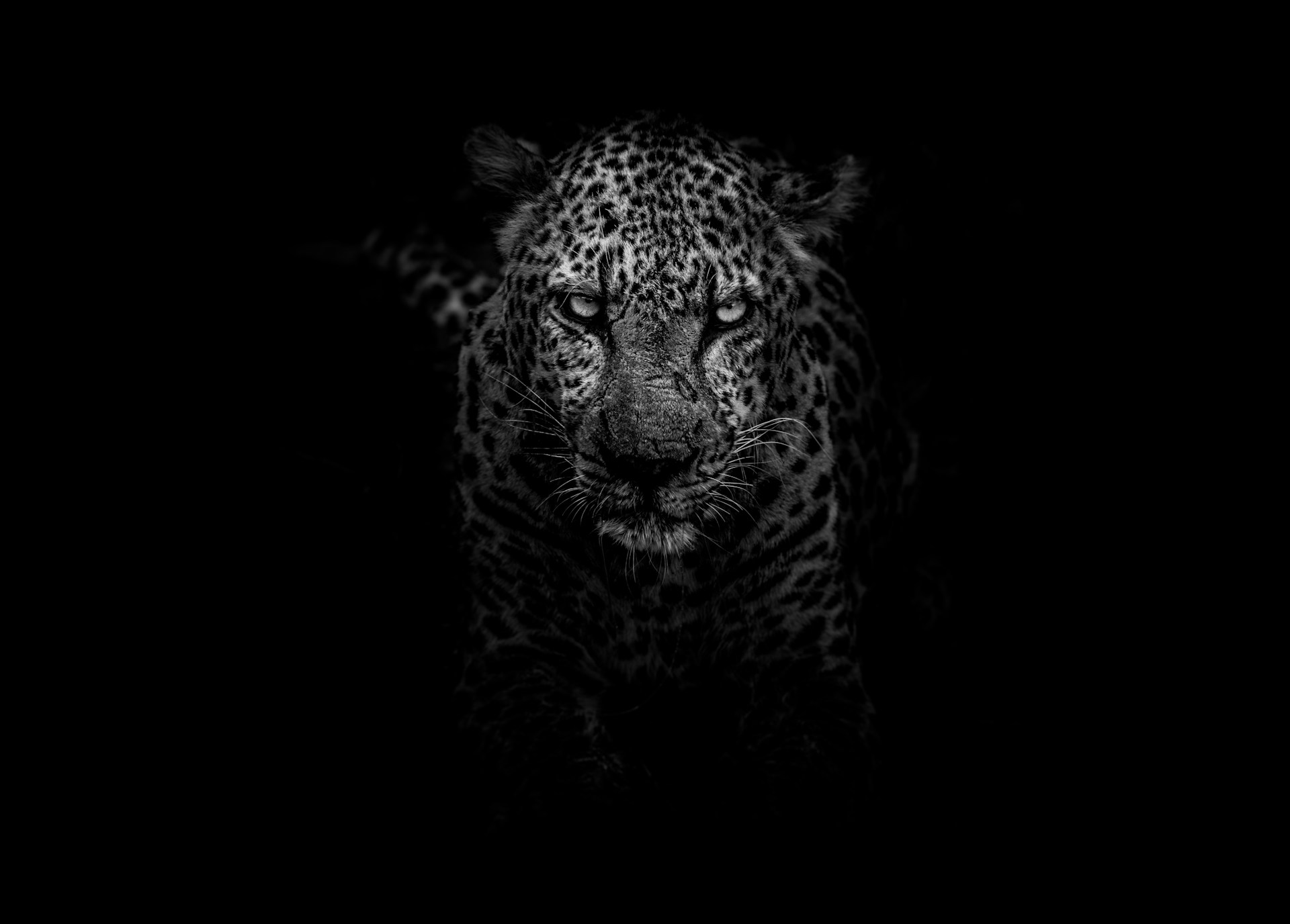

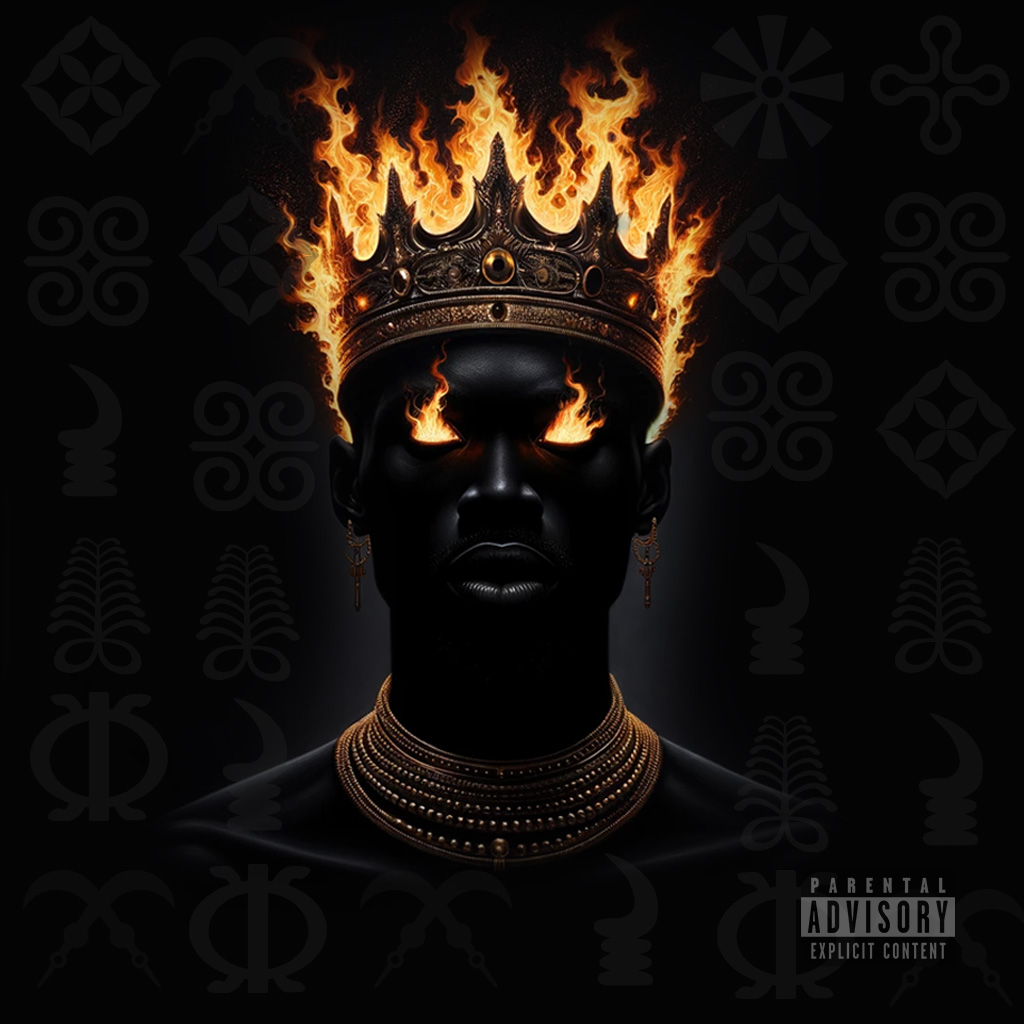

Welcome! I'm Yaw, dedicated to decolonising research.

An educator dedicated to decolonising design practices. Discover his work and ongoing projects.

The Challenge

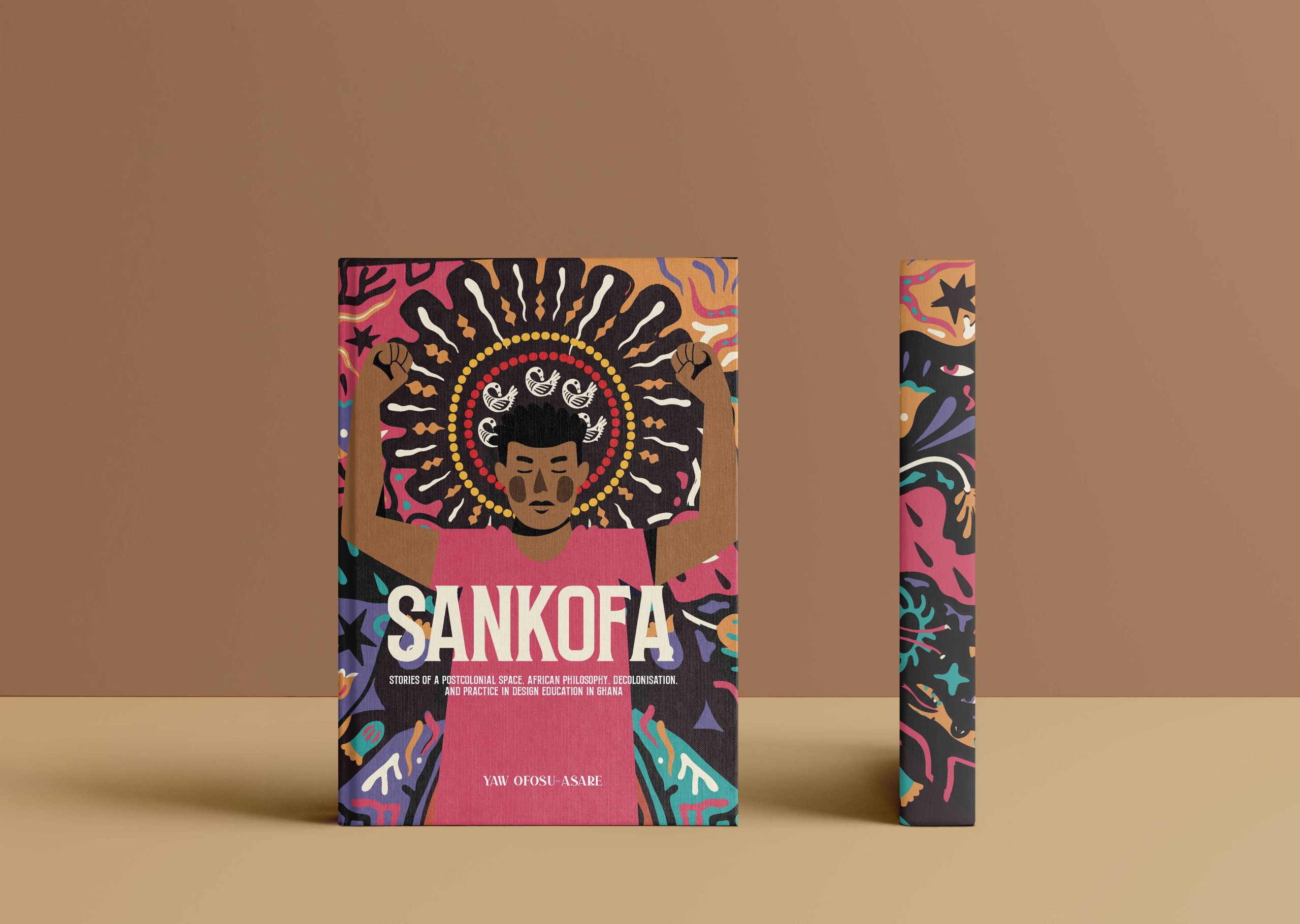

Decolonising design education addresses the deep-rooted colonial influences in academic and creative fields. Traditionally, design has been dominated by Western perspectives, often overlooking indigenous and non-Western styles. This limits the scope of design and its relevance globally. The key challenge is to break down these biases and create a design education that is truly global and inclusive.

The Approach

To tackle this, education programs must revise their curricula to include indigenous knowledge, local histories, and diverse cultural expressions. This will help broaden the understanding of design’s role in society and increase appreciation for its cultural aspects. Also, working together with different cultures can enhance design thinking and practices. By adopting a global perspective, design education can serve as a bridge for cultural exchange and innovation, preparing designers to create work that is both locally relevant and globally resonant.